Bojack Horseman Season five deconstructs its eponymous character, examining the glorification of abusive yet tragically flawed men in entertainment.

Five seasons in and you’d think Bojack would be redeemable by now. He’s not a bad person but he’s not exactly a good one either. His repertoire of sins goes so far as to destroy the careers of the people that believed in him. Or ruining the relationships by sleeping with, or at least trying to hook up with, friend’s significant others. Usually in moments of weakness – which is a shallow way of justifying Bojack’s behavior.

But Bojack has also done good things. He comes through for his friends now and then – especially when they need it the most, built an orphanage, and showed that he could be a decent father.

It’s humanizing in a way. Bojack’s intentions are often honorable, yet his actions tend to execute otherwise – often backfiring, failing, or hurting the very people he cares deeply about. Bojack is a toxic person. But what’s captivating about the series is how much he doesn’t mean to be. His actions, shitty as they may be, are justified by his dramatic backstory. In what is one of the most authentic depictions of self-abuse and addiction portrayed on TV.

The show is this metanarrative struggle about how difficult it is to change. How easily susceptible we are to the downward spiral. Granted, we don’t always go on a luxurious drug-induced bender like Bojack, but slipping is something everyone can relate to.

Bojack is needy, severely depressed and above all else: incredibly lonely. He lives with the guilt of being… himself. It’s humanizing to a fault. Which is odd given that the series is a dark comedy about anthropomorphic animals working in the entertainment industry. Though it’s this sort of tragedy that makes the series so compelling.

Last year, Bojack had a bit of a redemptive story arc taking a break from the bustle of Hollywoo and beginning the steps toward healing. Mostly, as a result of coming to terms with his parents and playing reluctant father himself, for a little.

His friends and support system, all started their own unique arcs toward success that ironically, showcased some of the cracks in their characterization and relationships. Maybe it wasn’t just Bojack? The tone of the series is very much about how susceptible we are to unhappiness. That life is variably complex and wallowingly sad. Especially when self-reflecting upon wanting to change.

There is a beautiful sadness in having everything yet finding meaning in absolutely nothing. It’s very Hollywood in style, with art and themes of the artificiality that is the entertainment industry. How easy it is to demonize ourselves to justify shitty behavior.

The series has gotten so popular, in an unprecedented move, Comedy Central has syndicated the Netflix series. With good reason, as without a doubt, I’ll say Bojack Horseman is one of the most enticing dramas I’ve watched on television. And I don’t say that lightly.

Bojack Horseman Season 5

Season 5 starts with Bojack on a TV set shooting, ‘Philbert’. It’s sort of a parody of dramatic crime shows, self-referential meta-fiction and a whole lot of dramatic tropes in between. There’s a lot of allusions to CSI, procedurals being set in almost every setting imaginable (Think walking dead and 24 level apocalypse situations), and even Mr. Robot (With a not so subtle Rami Malek cameo this season poking fun at himself). What’s ironic is that the set is a replica of Bojack’s home – creating this blurred line between reality and fiction – of its character participants.

It’s brilliant in its self-referencing drama. With one major arc being that Bojack, as he spirals yet again, cannot differentiate between reality and fiction. Though why should he? The show glamorizes his behavior and character – this flawed person established the past four seasons, and in a brilliant and unprecedented way…

Ties it into the #MeToo movement.

That’s right. This season takes this flawed character we’ve grown to love and puts him smack into the middle of his own #MeToo situation. Which is fitting to the tone of the show, but it’s also unprecedented because we start to look at it from the lens of the abusers and the culture of Hollywood itself – often how hypocritical it can be, and how it glamorizes overt sexuality in the context of character development.

In the season opener, we see BoJack complain to director Flip Mcvicker (Rami Malek) as his co-star/girlfriend Gina (Stephanie Beatriz), critiques the series as “gratuitous and male gazey”, particularly with it’s oversexualized portrayal of female characters (Think Game of Thrones seasons 1-3). As a result, they cut some of the other female sex scenes, then call for nipple ice as they immediately focus on a full frontal nude scene for Gina herself – because it’s acceptable if the nudity is character-centric as it develops context.

In another episode entitled, “BoJack the Feminist” BoJack accidentally calls out his co-star Vance Waggoner (Bobby Cannavale), a character designed to be the worst of Robert Downey Jr., Louis CK, and Mel Gibson combined. Bojack is praised once he realized that that problem with feminism is that “men weren’t doing it”. He ironically becomes the face of the feminist movement.

Later on, Diane is hired to make Philbert more rounded and represent women better, only to be shafted and put in a corner office meant to keep quiet. And even though her eventual breakdown and efforts to fix the show lead to great success of the series – she’s never given any serious credit.

This season is all about how women don’t get a say in the entertainment industry. How belittled they are by their male cohorts. Gina is not at all happy about how the events of this season unfold yet continues to fake smile and press forward because “Philbert” for better or worse, is the highlight of her career.

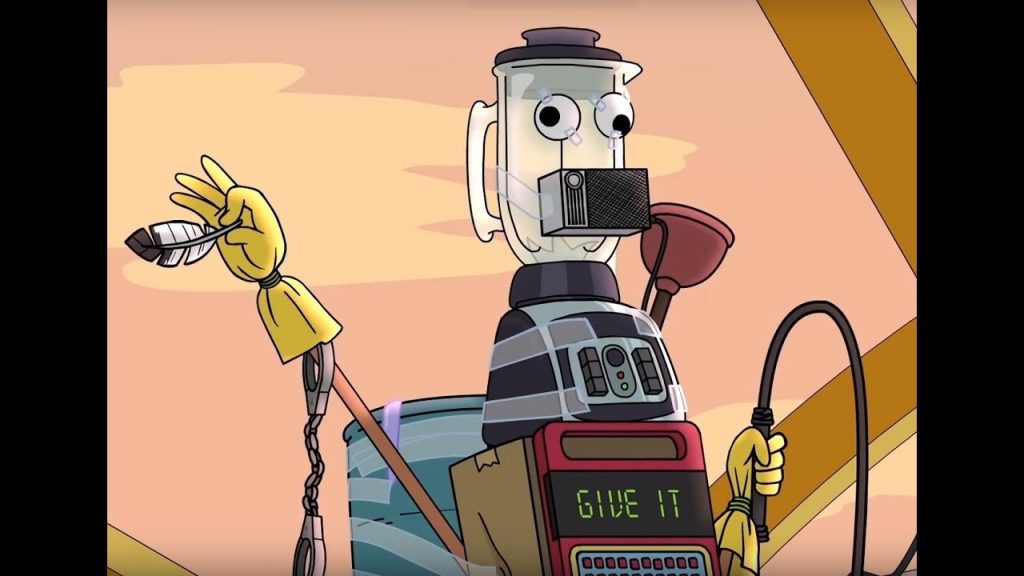

In a not so subtle joke, Todd gets in yet another wacky adventure and creates a literal sex robot in a naive attempt of helping a friend. Hilarious antics ensue as always in a Todd B-story, but what’s most disturbing is that the sex robot fails upward to become the head CEO of the company producing Philbert, in a direct reference to how easy it is for these Weinstein like sexual predators, to succeeded where women have always struggled.

Style

For five seasons, we’ve watched Bojack Horseman, this washed-up TV actor that more than resembles Bob Sagat, struggle with addiction and the inability to be happy. Though rather than continue episode-by-episode in sitcom or even traditional story drama format, the series has very much utilized its animation medium and unique sense of writing.

The season cliffhanger drives the writing. Season one goes into two with filming Secretariat, this dream project about BoJack’s hero and perhaps his last shot at being a serious actor. Two into three, was BoJack’s Oscar push, this idea that the award would finally be something of meaning in his life. Four was a bit of a damage control break. Featuring the Hollyhock storyline and finally seeing the environment BoJack was raised in. We understand just how damaged his family was and how he ended up that way.

But it’s more than BoJack’s main arcs. Over the years, we’ve seen Princess Carolyn develop as she’s gone from ace agent to an older woman, struggling with starting a family of her own and not know how to balance the act. She’s doing her best to adopt a child this season, and we get snippets into her own backstory. It is subtle yet impassioned, as we realize Carolyn comes from simple roots, and see that she’s spent a lifetime managing other people. Her success, necessitated out of her own survival of being an independent person – though one that’s often just as lonely as BoJack.

Mr. Peanutbutter and Diane’s stories have always been a gem of seeing the difficulties of marriage. This season has them finally divorced yet still developing on their own. In a hilarious Halloween party episode, that takes us through several time-sensitive and pun-filled flashbacks, we see that the gallant yet happy-go-lucky Mr. Peanutbutter has always had his own developmental problem. His childlike positivity comes at the cost of his own ability to grow up and take responsibility.

Diane goes to find herself this season, traveling to Vietnam to find her roots in an episode styled like sex in the city or Eat. Pray. Love. Though its conclusion is sort of isolating. It’s oddly representational, having Allison Bree, a white woman, play a Vietnamese woman feeling isolated from her Vietnamese American family. The Bostonian roots feel more rooted in its anti-culture than any sort of familiarity with being Asian. The series feeling intentionally alienating.

And of course, there’s Todd. He’s coming to grips with his asexual identity, seeking partnership yet also still being… Todd. There’s an episode where he meets his asexual girlfriend’s family – who happens to be openly sex-positive, in one of the season’s funnier bits about sexual identity.

Though his episodes are heartwarming, Todd’s always played more of a fun B character who accentuates the more prominent story arcs. This season, Todd rises to a position of authority, mocking a problem with modern Hollywood. How brainless nobodies call the shots and how unfortunate that can be – particularly for women. This season is more about Todd’s reluctance to act or say anything against his new boss. A boss Todd built personally: his recently assembled then discarded sex robot, Henry Fondle (Todd built it for his friend, but he himself knows absolutely nothing about sex).

One of the prominent things about the series is how well the animation accompanies the writing in a unique blend in style. We’ve seen it time and time again. The show will play from a misleading point of view to fool the audience, like Princess Carolyn’s granddaughter from the future or Diane’s book that was never an actually written book, and showcase dominant themes about how artificiality and the dream itself – often a metaphor of Hollywoo culture – is much more influential than reality. Because life is bleak at times… So the animation leads us on a misleading adventure to help us forget.

Though the creators don’t shy away from more grounded stories. From the much acclaimed underwater episode, where BoJack wants desperately to apologize to Kelce for being fired and everything is shot without a line of dialogue, to this season’s “Free Churro” written as a three-act eulogy with no cutaways about BoJack’s now deceased mother, and how the death of a parent influences you… even if it’s a reviled parent.

Again, I can’t understate how powerfully dramatic this show is. Though I should also mention, perhaps the most memorable of the series’ episodes have been BoJack on his benders. Where reality blurs and we see him confronted by his manifested psychological issues – usually through drug-induced hallucinations. Last season, “Stupid Piece of Shit” was a beautiful blend of Bojack’s self-critical inner voice and animated scribble-like drawings of self-loathing – mostly while he was drunk.

But the most tragically beautiful and memorable, were BoJack’s episodes featuring Sarah Lynn. They usually include drug tripped hallucinations and time lapses, allowing for flexible storytelling. They also are some of the most powerful episodes of the series. We see BoJack, vulnerable and screwing up his life yet again – but in context, can also understand why he goes on these binges.

The damage it causes though… it’s horrible yet also, human.

#MeToo

Which is where the most humanizing and polarizing arc is in this season. BoJack gets into an accident this season, which leads into a season-long addiction to painkillers. We see him confronted with his identity. How glamorizing his shitty behavior and life choices, and then adapting it into a show about himself, which ironically is what the BoJack Horseman series is about: drives him insane.

BoJack loses who he is in the character. He is overworked, severely depressed, and his relationships are coming apart. Especially, once some of his past comes to light to haunt him…

He is alone. And in default BoJack fashion, we see him overindulge. This leads to some of his most reprehensible actions to date. BoJack assaults a woman. And it’s not funny. Though we also sort of understand the events that lead to him doing it…

Which is why this season is powerfully compelling.

Diane mentions towards the end of the season… that she didn’t expect her writing in ‘Philbert’ to glamorize the actions of shitty people. By making them human, and therefore, forgivable we normalize the culture into forgiving these monsters. As if everything they’d done was okay. It’s a bold statement about Hollywood. And we see the person we’ve come to truly feel for, in BoJack, do something utterly horrible. And we don’t know how to feel about it.

The Take

It took me a long time to write this. As someone that used to work in the mental health field, substance and sexual abuse are subjects I take to heart. I’ve seen many lives ruined by it. I’ve also heard many stories of redemption. Which is why I think season five was an essential message for the culture of entertainment. It addresses the topic abuse, both substance and sexualized, and reforms it into a critique of the entertainment world.

It is without a doubt, one of the most authentic depictions of self-abuse I have ever seen. Humanizing both the victims and the abusers, while making us realize how tragically flawed we can be.

Bojack Horseman makes us address our darker moments. How we deal with our indignities and the sins of our past. Life is complicated. It doesn’t always work out the way we think, and for the most part, we’re barely keeping it composed. But this season seals it. That all the drugs and debauchery and awards can never fill that void of guilt and isolation.

Because when you hate yourself so much. Because when you continuously question if any of us are good people? You have to acknowledge that there might be something broken inside. At least, I think so.

Bojack is an odd show about beautiful sadness. This season is as equally funny as it is depressingly captivating.

You can watch Bojack Horseman steaming on Netflix.