A look at different types of representation for Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month

When I was a kid, I scoffed at the idea of media representation. I figured, if a story is good, it’s good. We’ll get whatever characters and actors we get; their race and gender shouldn’t matter.

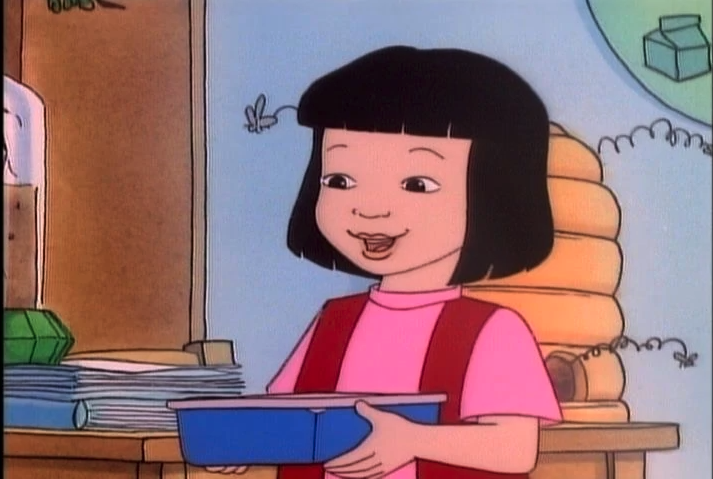

Much later, I realized representation did make a difference, even if I didn’t think about it at the time. Why else was I so excited whenever there was an Asian character, like Wanda in The Magic School Bus or Cho Chang in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire? Why else did my friends and I think it was so cool that the band Linkin Park had an Asian rapper? “Hey, it’s one of us! We’re not just some flat stereotype. We can go on adventurous field trips and learn magic and create popular music, too!”

It’s important not only for inspiring ourselves, but also to show others that we exist. We are capable, diverse, dynamic, and just as worthy.

Yet not all representation is good representation. There have been some pretty awful cases like Mr. Yunioshi in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) and Long Duk Dong in Sixteen Candles (1984), where Asianness itself was the punchline and it caused us to be viewed as less than human. Sometimes we have unique stories, perspectives, and experiences to share and celebrate. Other times, we just want to be viewed as regular, everyday people. Never should Asianness be weaponized to alienate and detract.

Nowadays, some occidental films with Asian leads have performed very well in the United States and elsewhere, such as Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle (2004), Slumdog Millionaire (2008), Crazy Rich Asians (2018), Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings (2021), Turning Red (2022), and Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022).

It’s awesome to see these films succeed. I’m deeply appreciative of these works and everyone who supports and enjoys them. But I also think there’s even more that we can and should demand of future productions.

Read on for four different ways to do Asian representation right in television and movies. Maybe you’ll find something new to watch this weekend, too.

Original Asian stories and characters should stay that way

I consider this the bare minimum for Asian representation. Our narratives and characters ought to be respected as our own. No one would dare to cast a white woman in a live-action remake of Mulan. So why do some people think erasure of other Asian characters is acceptable?

Sighs of relief for not messing this up: Olivia Munn as Psylocke* in X-Men: Apocalypse (2016); Karen Fukuhara as Katana in Suicide Squad (2016); Lana Condor, Janel Parrish, and Anna Cathcart in To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before and its sequels (2018, 2020, 2021)

Face-palms for erasure: Emma Stone as Allison Ng in Aloha (2015), Scarlett Johansson as Motoko Kusanagi in Ghost in the Shell (2017)

Of course, in art it is very common to draw inspiration from stories and cultures all around the world. This can make for compelling, meaningful new tales or mash-ups. That’s not what happened with these face-palms, though.

*In the comics, Psylocke is both a British woman named Betsy and a Japanese woman named Kwannon. I thought it was pretty neat that they cast half-Asian Munn for the role.

Asians should get to tell more of our own stories

We’ve seen this with Turning Red, which I mentioned earlier—and which we’ve reviewed here on The Workprint in case you missed it. Writer and director Domee Shi created the film based on elements of her own life in Toronto.

Other examples of great original movies written by Asians are Better Luck Tomorrow (2002) by Justin Lin and Ernesto Foronda; The Farewell (2019) by Lulu Wang; Always Be My Maybe (2019) by Randall Park, Ali Wong, and Michael Golamco; The Half of It (2020) by Alice Wu; Definition Please (2020—also check out our review) by Sujata Day; and Raya and the Last Dragon (2021) by Qui Nguyen and Adele Lim.

In television, we have Fresh Off the Boat (2015–2020) by Eddie Huang, Kim’s Convenience (2016–2021) by Ins Choi, and Awkwafina is Nora from Queens (2020– ) by Awkwafina and Teresa Hsiao.

It may seem like a lot already, but there’s such rich depth and breadth to Asian and Asian-American experiences (or -Canadian, -British, etc.) that there’s far more still to articulate.

Also, I’d love to see us bring more of our creations in other genres to the screen, such as science-fiction. It would be cool to see something from the likes of Ted Chiang (whose novella “Story of Your Life” was adapted by Eric Heisserer into the 2016 film Arrival), Ken Liu, or Liu Cixin. In fact, Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem is already slated to become a major Netflix series with several Asians on the production team.

More characters without specific backgrounds should be played by Asian actors

Last year, Rahul Kohli (The Haunting of Bly Manor, iZombie) went on the Blackman Beyond podcast and spoke about representation in media: “When you send me for a role, and it says, ‘South Asian—his name is Raj,’ I go, ‘I don’t f***ing want it.’ Then the next one comes in, and it doesn’t have a race. ‘This is John. Thirties. Handsome…’ When it says that, I go, ‘Oh, they’re seeing everyone. I want that f***ing role.’”

This is what I meant when I said earlier, “Other times, we just want to be viewed as regular, everyday people.” Why should a generic character, a cultural blank slate, default to white? When characters are written without anyone or any particular background in mind, more of them should be played by Asians.

When I watched Steven Yuen play Squeeze in Sorry to Bother You (2018), Kelly Marie Tran play Rose Tico in Star Wars: The Last Jedi (2017) and Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker (2019), and Rahul Kohli play Owen Sharma in The Haunting of Bly Manor (2020)—none of these roles felt particularly Asian. And that’s a great thing, too.

There should be more than one Asian character, and they should talk about their Asianness at some point

If my four forms of Asian representation were a Maslovian pyramid, this one would be at the very top. Obviously I’m not talking about media from or exclusively about Asians, like Crazy Rich Asians or even Indian Matchmaking (2020– ). I’m looking at broad-based, run-of-the-mill, “all-American” works. Think of it as a sort of Bechdel Test but for Asian representation.

Season 2 of Love is Blind (2020– ) unlocked this achievement when cast members Deepti and Shake got engaged. They connected on their dating histories, families, and culture in a way that only two Indian-Americans could.

The only other example I have for this comes from Dollface, a comedy series that premiered on Hulu in November 2019. The main character is played by Kat Dennings (Thor, WandaVision, 2 Broke Girls), and two of her closest friends are played by Asians Brenda Song (Wendy Wu: Homecoming Warrior, The Social Network, a ton of Disney and other stuff) and Shay Mitchell (Pretty Little Liars, You).

At one point in season 2, Mitchell’s character asks Song’s, “Can’t we as Asian women own our own sexuality, too?” It was just a quick remark, and no one else in the show ever brought up race again. But it really struck me. Not only was it astute social commentary, but it also felt like an organic conversation in a realistic, relatable dynamic. It made me feel warm and fuzzy about the portrayal of Asian-American friendship on TV; I imagine this is how Black fans feel about Insecure (2016–2021).

Also, did you know Shay Mitchell is related to Filipina legend Lea Salonga, the singing voice of Princess Jasmine and Mulan?

Final Thoughts

Again, I acknowledge and appreciate that Asian representation in Western media has made enormous strides in recent years. Good representation can be tricky, and we have many more interesting characters and role models than before. I’m excited to see how this trend will continue over the years to come.