In this episode, we go over the Monomythic storytelling structure.

I’m going to let you in on a little secret: every story ever told has been told in some another shape or form. Stories are universal. They date back to the oldest of traditions and are passed down through different forms of art and culture. They’re fundamental to being human as every person is a natural storyteller. Stories are simply how we think about and interpret our world – whether we realize it or not.

If I asked you, “What did you do yesterday?” You’d begin by telling me a story. Maybe you ate breakfast, walked the dog, went into work, and afterward, had tacos for dinner. Congratulations, you just told me a story. Maybe it was something else? Perhaps it was something less conventional? Maybe you went into a job and did nothing but solve complex equations all day, looking for a new formula of rocket fuel in order to travel to Mars. It might be more math related, and thus, personally, something I’ll never truly understand, but that’s still telling a story. You’re still out there doing things.

Every memory, every experience, and every type of thinking where ‘you’ (literal or projected onto another: aka empathy) is involved in performing an action is a type of story. Humans are natural storytellers because it’s how we conceive of the world around us related to ourselves.

The Monomyth

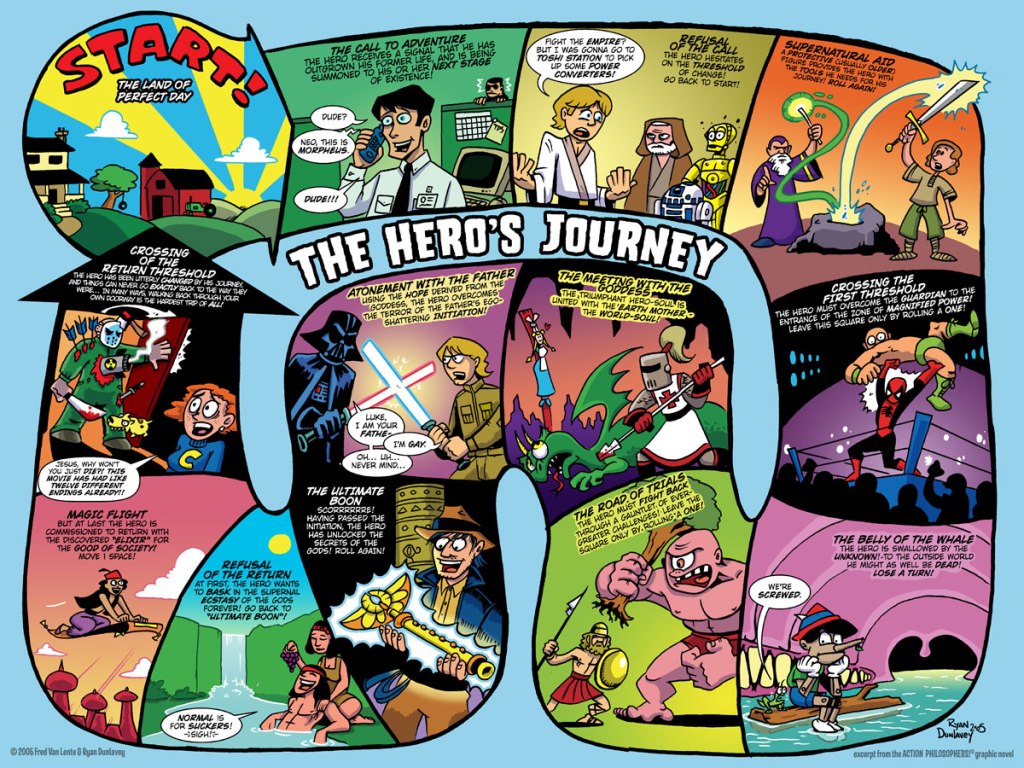

This lesson has been a long time coming. It’s the foundation of this blog, as well as the reason why you’re here. This is how you tell a story according to the Monomythic Structure of Joseph Campbell’s Hero With A Thousand Faces.

It’s important to note that not every step needs to necessarily be used. If anything, think of the Monomyth as more of a guideline.

Also, for every segment below, I’ll be talking about, I’ll be referring to Hero as a gender-neutral term – because that’s only fair.

1. Ordinary World/Call to Adventure

This is the world before. Where the protagonist is before the story begins. It is their safe space and where we learn about the main character: their personality, abilities, and perspective on life. It’s the part in the movie where we sympathize and understand exactly who this person is and how we relate to them. It is where we will empathize with them the most. Usually, this is where we will see your character in school, at their job, and with their family – understand their status quo before the call to action.

Then, something happens. Their status quo breaks. This could be meeting the love interest in a romance, or getting the ticket to the Titanic, losing a well-sustained job, or entering cryogenic sleep in the science fiction space chamber before waking up and finding the ship is now infested with aliens.

The Call to Adventure is exactly that: the thing which causes the initial change or necessitated change in the story – which will eventually propel your character forward.

2. Refusal of The Call

The hero may or may not be eager to accept the call but let’s be honest: change is uncomfortable. At this point, your character may have doubts or second thoughts about whether they should be doing this. If that’s the case, the hero may refuse the call and suffer, like Luke Skywalker losing Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru. The goal of this moment in the story is hesitation. It’s the perfect time to make aware the stakes of what’s at hand but also give us a sense of the limitations of the main character – see what they can do versus what they are willing to do, at this point in the story.

3. Meeting the Mentor/Supernatural Aid

It’s straightforward: this is when we meet the mentor figure. The person who helps guide the hero into making the decision and sets them on the path. Whatever the mentor provides, it helps the hero believe in themselves to take the necessary journey. Often, however, the Mentor also provides a degree of magic and supernatural aid – though more in the sense that they introduce them to elements of a world they’ve yet to understand.

4. Crossing the Threshold

The main character crosses the threshold of the familiar world and begins the journey entering the unfamiliar world. It can be a small dip into being a superhero. A foray into a talent one hadn’t expected to be good at; Or even the beginnings of an emotional, mental, or physical journey.

It can be the first step in traveling to a new destination or taking on a task the protagonist has always been afraid to do. The goal is that this will be the first step of a new world of experience.

5. Belly of the Whale

This is the point of no return. It’s crossing the Rubicon. Or entering the belly of the beast. It represents the final stage of separation from the known world. From here on out is this new experience – whether it be a new relationship, quest to destroy the ring, or whatever lies ahead. This is the beginnings of the hero’s metamorphosis.

6. The Road Of Trials: Allies, Tests, and Enemies

The protagonist is then confronted with a series of tests and challenges. Obstacles that bar the way which can stop them in their tracks. The main character then needs to push through everything to overcome this, pass their tests, and continue the journey towards their end goal.

Yet to do this, they not only need resilience but also: awareness. This is where the hero learns who to trust, builds allies, and makes enemies – forming bonds with people who will help along with the trials ahead.

These lessons and experiences will then help forge the character into becoming who they need to become, provide greater insight, but more than anything else: help them grow as a person.

It’s also some of the most exciting parts of the screenplay as it’s where your main character starts turning into what you had promised in the movie trailers.

7. Approach to The Inmost Cave/Meeting with The Goddess

Honestly, this entire thing sounds like a euphemism for a vagina. Given the psychoanalytic influences, I don’t think that it’s much of a stretch.

The inmost cave is supposed to represent the ultimate goal of this quest. It’s not a literal location, but a representation of the large trial the hero must undergo in order to obtain their objective. Approaching it usually requires a lot of preparation. Which is why you should think of the ‘approach to the inmost cave’, as the calm before the big storm. The moment where the hero reflects on everything they’ve now gone through since crossing the threshold.

A lot of the anxieties from the ‘Refusing the call’ section of the character’s life before will manifest again here. It’s where the audience is reminded what the protagonist is capable of doing (which should be more than before) but also, should reflect on what’s at stake – which by now, may seem like an even bigger threat than when the protagonist first started.

The ‘Meeting with The Goddess’ also takes a slightly odd interpretation by contemporary standards. From my understanding, the Cave and the Goddess are somewhat synonymous (again, vagina), however the Goddess can also be interpreted as a quite literal meaning: as it’s supposed to represent what the protagonist needs at the moment to feel whole again.

Sometimes this can be as simple as finding an Oasis in the desert. Or perhaps it’s even just a break from all the fighting. Often in Hollywood, this is where one of the allies picked up on the road of trials reveals themselves as a potential romantic love interest (have I mentioned vagina enough?), and in the even more traditional sense: provide a potentially promising life with the protagonist in a happily ever after situation.

8. Temptation

This should be straightforward: instead of finishing the task at hand, why not run away together? This is in myths, the moment where Circe or Calypso holds onto Odysseus. The moment where the hero is tempted by a female in abandoning his quest.

To be frank, this one isn’t all too utilized in Hollywood screenwriting anymore; however, I will mention it here because I am acknowledging that it exists in the original Monomythic structure. Unlike many sources which try and shy away from the poorer looked upon sides of the material, I am acknowledging that it exists – again, story formulas are never perfect.

9. Atonement with The Father

This is usually the big showdown. It’s confronting the thing that killed Inigo Montoya’s father. It’s making the family proud by conquering the thing that has control over the protagonist’s life.

Symbolically, this is seen as the father. At least, according to the original Monomythic interpretation. However, for all intents and purposes, ‘The Father’ is really just the thing in the protagonist’s life that represents control over life and death.

Which is why the atonement moment is usually synonymous with the big trial and test ahead of the hero. It’s the moment they have to call upon all of their newfound powers, skills, and experiences to overcome the greatest challenge – essentially atoning with the father – though sometimes quite literally, as seen with Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader.

10. Apostasis

And in order to beat the demons of the past: Your character is going to have to die…

Yep.

Basically, your character must undergo some form of metaphysical death in order to be reborn again. A resurrection that allows them greater power and knowledge, necessary to fulfil their destiny and reach their journey’s end.

This is the exact opposite point of where your hero started in the story. It’s the climax in which the hero has ‘atoned with the father’, confronted the demons of the past by accepting the frailty of their own life, and are now having their most dangerous encounter with death (And when I say death I really just mean, the worst-case scenario imaginable. Though death often fits that category).

It’s also the moment where the hero realizes that there’s more to their decisions than just their life. Their actions have consequences that affect the lives of others including the ones they care about, but also, have consequences upon their world at large.

So ultimately, this is where your hero succeeds, vanquishes their demons, and emerges reborn as a type of golden God or Goddess. This is their moment of triumph.

11. The Ultimate Boon

The hero is transformed into a new state and is thus, able to reap the rewards for vanquishing their big bad demons. The reward can come in many forms: objects of power, deep romance, hidden treasures, greater knowledge, or reconciled sins now forgiven and atoned for. Whatever it is, the hero is going to bring it with them back to their ordinary world.

12. Refusal of The Return

This echoes the call to adventure but in reverse. This is the moment where the protagonist is supposed to return, though often hesitates, as at this moment in time, they’re feeling at their best and perhaps don’t want to return to the world before.

Regardless, the important part is that the character must make a choice, then commit to their cause as the last steps of the journey take place.

13. Magic Flight

This is the first step to return into the world before. Though remember, having to get back isn’t exactly easy – The Odyssey was literally an entire story about this. It can take a very long time sometimes. In many movies, this is usually the final flight out of a hostile situation, avoiding the big explosion, or the order to evacuate. Whatever the case, it’s intention is usually one thing: to get out of there and retreat home.

14. Rescue from Without

Often, the Hero needs help to get back. Just as they needed the mentor to push them forward, they’ll usually need a friend to help them return home. Think the Eagles at the end of Lord Of The Rings. Or Han Solo saving Luke by clearing the path during the Death Star run.

15. Crossing the Return Threshold

At this point, the character has returned into the old world and are officially where they were prior to leaving on the journey. This is Frodo heading back into the Shire. This is the moment the kids return home not ever knowing if they can go back to Naria.

16. Master of Two Worlds

The character looks back and reflects, having achieved mastery of both worlds. They’ve grown from their journey and can share the lessons and wisdom from what they’ve learned: things significant enough to make a difference in their immediate world.

Likewise, whatever problems they had before… are not the same anymore. They’ve changed. They’ve grown up.

17. Freedom to Live

Having mastered both worlds and gone through the journey, the character is now able to live freely with an unprecedented degree of authenticity. They can live out their lives however they see fit, knowing about what it’s like on the other side of life.

Try This: Find a Monomythic Adventure

- This one is a complicated lesson, so this is my only assignment: Find as many movies as you’d like that fit the Monomythic structure. List how they fit into it.

If this all seems confusing and messy, don’t worry. Next week, we’ll be going over Dan Harmon’s story circle – which is basically this, but simplified.