What is a conductor anyway? Musician, interpreter, dancer, magician? The funky person in formalwear who waves a stick in front of an orchestra?

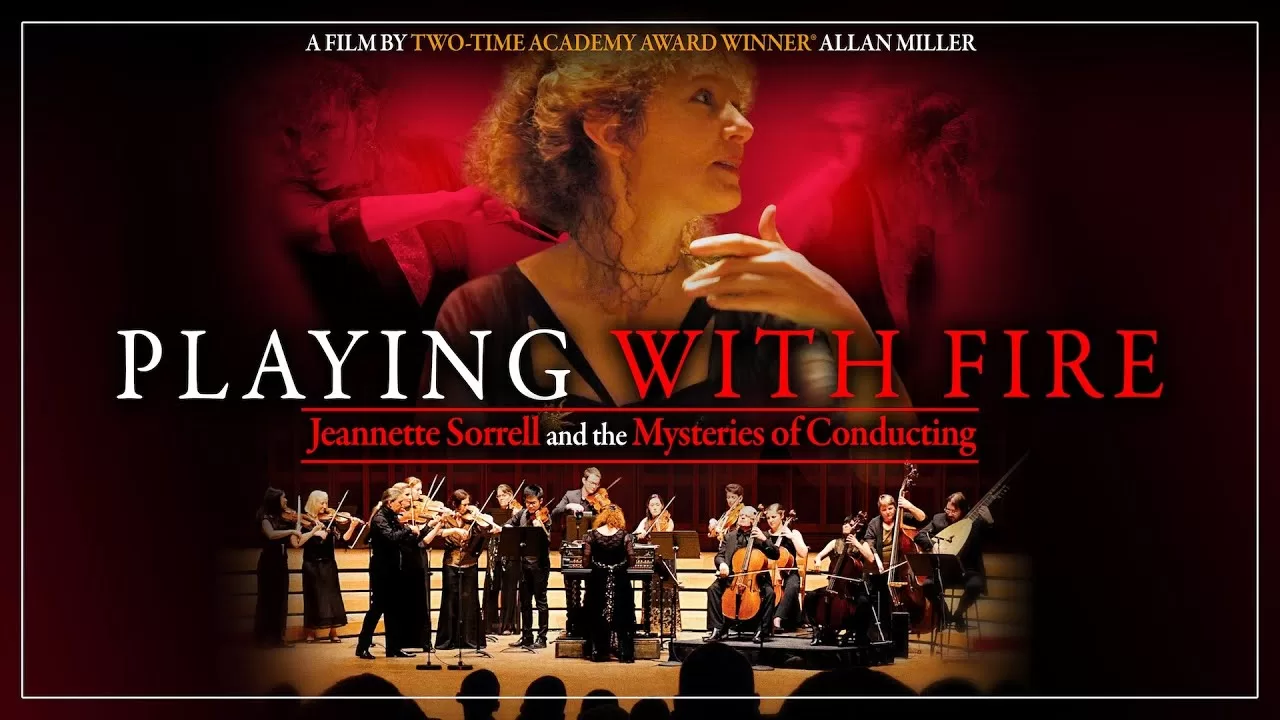

In Playing with Fire: Jeanette Sorrell and the Mysteries of Conducting, two-time Oscar-winning director Allan Miller explores this question by painting a vivid portrait of a woman who spends her life bringing the subliminal secrets of music to life for us mere mortals to hear. Told at a young age that no orchestra would hire a woman conductor — and rejected by an actual orchestra on the basis of sex alone — conducting prodigy Jeannette Sorrell went on to form her own chamber orchestra, Apollo’s Fire, to bring Baroque music to life on period instruments, then wow the classical music world with her talents.

Wait, but what is Baroque music? If you watch any kind of TV or film, you’ve certainly heard it — that old time-y soundtrack to elite functions, often used in contemporary media to denote prissiness. Violins and harpsichords and oboes. The music of Western Europe from about 1600 to 1750. Bach, Handel, Monteverdi…

It can be difficult for contemporary audiences to understand the passion and subtleties that lie behind the precisely performed melodies, shimmering over harmonies engineered for mellifluence. Playing with Fire takes a deep dive into how those who’ve dedicated their lives to this style of music experience it — how a melodic passage can represent climbing onto a horse, or how a chord can be as ominous as the slamming of a dungeon door. The film often presents Sorrell’s explanation of what she hears in the notes, then steps back to give the audience a chance to hear what she hears.

The documentary follows Sorrell as she rehearses, performs, and teaches, showing the process and mindset behind what it takes to look at a page of black-and-white ink and transform it into sounds an audience can understand. How she speeds up or slows down the orchestra through her expressive yet precisely timed gestures to breathe life into a piece. How she uses storytelling and metaphors to help her musicians and students understand her vision.

The power of her conducting becomes especially clear when contrasted with the relatively rough movements of the novices she teaches — a moment that, coming late in the film, highlights her talents by showing how awkward and at times robotic a less experienced conductor can appear in comparison. Through this and other subtle techniques, the documentary shows what it wants to tell, giving the audience a chance to see for themselves what a good conductor can do.

While Sorrell does give a few personal anecdotes in her interviews, and a few moments are dedicated to the business of classical music, Playing with Fire primarily focuses on her art — how she approaches conducting, what she’s trying to get out of the score. Those already familiar with classical music will find the film a fascinating look at a conductor’s process. Those less familiar, however, may find it difficult to follow at times, as Sorrell enthusiastically rattles off Italian music terms with nary an definition in sight.

It’s difficult for anyone to describe exactly what a conductor does because there are so many nuanced actions, so many undefinable pieces that go into turning the transcendent into reality. That makes the difference between a computer playing pitches louder or softer and a true musician giving that same set of pitches, a soul. Through its portrait of Sorrell, a uniquely gifted and uncommonly dynamic conductor, Playing with Fire proves that it’s up to the challenge.