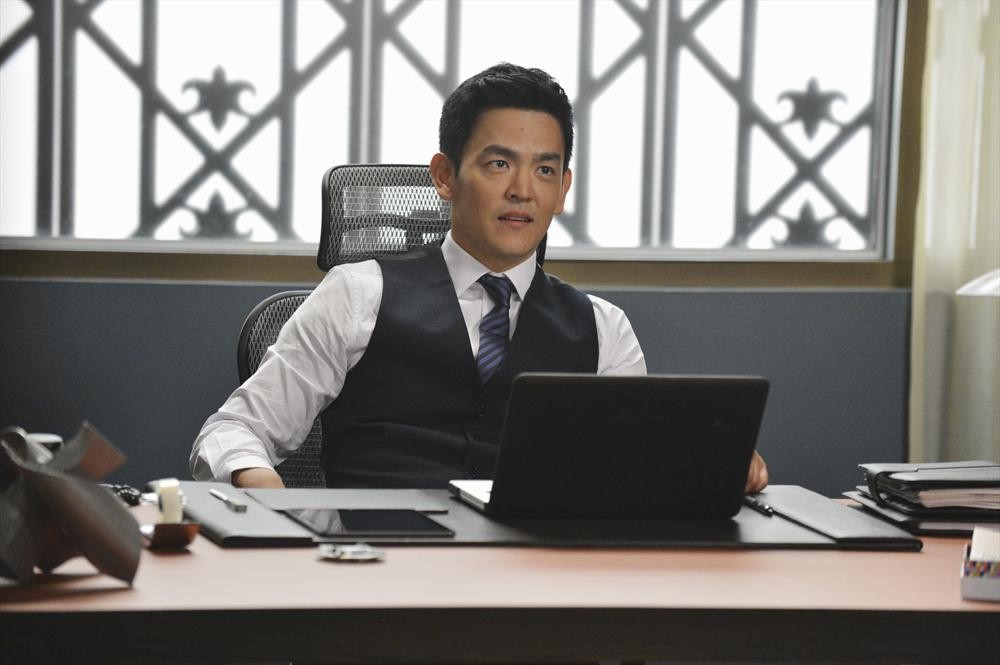

ABC’s new comedy ‘Selfie,’ is a reimaging of ‘My Fair Lady’ for the digital generation. Karen Gillan stars as Eliza Dooley (get it?), a pharmaceutical sales rep who realizes that all her Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram followers don’t stop her from being lonely and friendless in real life. She enlists the aid of co-worker Henry (John Cho)—a marketing genius—to “re-brand” her as more likable and help turn her IRL social life around. Sadly, Eliza’s “re-branding” is rooted in sex panics, high-handed moralizing, technophobia, and tired old stereotypes about the sexuality of women and the asexuality of Asian men.

Bullied as a teenager for being—as she describes—“butt,” Eliza has reformed herself in the image of social media, becoming Instafamous and garnering the popularity she so desperately coveted in high school. Eliza’s dedication to her online presence has forced her to neglect her offline relationships and made her narcissistically obsessive. This has made her blind to the fact that the bullying she tried so desperately to escape has followed her from high school to the workplace. She is constantly ridiculed for her intimate connection to her phone, and her real-life social awkwardness is traced back to her slavish devotion to her online world. This not-so-subtle critique recalls the oft-invoked technopanic rhetoric that links the “downfall” of social manners, interpersonal communication, and work ethic brought about by the constant connectedness of the Millennial generation and their successors. Eliza explicitly references this generationally motivated, and media perpetrated, conflict when she states: “Social media can be confusing if you are old and dumb.” It is a line that simultaneously panders to younger audience members while legitimating the presumed prejudices of older ones.

A key to Eliza’s transformation is her embracement of her body, her sexuality, and her desire. So of course, the other characters on the show treat her as the office slut. She is the firm’s top salesperson, so her co-workers assume she sleeps with all her clients to ensure their business. When her revealing office attire fails to attract a warning from human resources, her co-workers decide she gets special favors because she has slept with the entire department (yes, the whole department. I guess they subscribe to the mantra “go big or go home”). Henry, upon meeting her for the first time, tells her that she has “lose sexual morals,” a conclusion he has drawn after listening to office gossip about how she attempted to date a man she did not know was married. In the second episode he informs Eliza that she is a “booty call” because she has had two (!) relationships that he knows about. Quick, someone get this woman a scarlet A and start handing out the penicillin.

Taming Eliza’s overt sexuality is Henry’s primary goal when he agrees to assist her with her transformation. He admonishes her to not make everything so “lurid” and “sexual.” He instructs her to dress for a wedding with less make-up, less cleavage, and more fabric. He covers her from the waist down with his suit jacket when he deems her office attire to revealing. He chastises her for not following his rules and explicitly disobeying his lessons. He is overwhelming paternalistic, acting towards her the same way an exasperated and out-of-touch father would his teenage daughter. Henry’s “great transformation” playbook has three moves: shame, patronize, and preach. To be fair, that may not entirely be his fault, because in line with long-held Hollywood tradition, Henry—as an Asian-American man—is written as an asexual character.

South/Asian and South/Asian-American men on screen have long been denied a sexual presence. They can be trusted sidekicks (Bruce Lee on ‘The Green Hornet,’ George Takei on ‘Star Trek,’ and Dani Pudi on ‘Community’), precocious man-children (Aziz Ansari on ‘Parks and Recreation’), an unhinged ball of explosive anger (Ken Jeong on ‘Community’) or a prank-loving reluctant time-traveler (Masi Oka on ‘Heroes’). What they rarely allowed to be is sexual (two notable exceptions are Daniel Dae Kim on ‘Lost’ and ‘Hawaii 5-0’ and Steven Yeun on ‘The Walking Dead’—more on Yeun later). Henry is no different. He is a closed-off workaholic who has put his career ahead of himself and his personal life. He seems uncomfortable with personal contact and after joining Facebook realizes that he is the only one of his friends not married with children. He insists that his interest in Eliza could never be sexual and in the same episode his boss says to him “You are always alone, it’s kind of weird.” And just to emphasize how buttoned-up he truly is, he literally buttons-up: his casual consists of shirts buttoned up to the neck and covered by a ‘Father Knows Best’ style cardigan sweater.

It’s clear that Henry and Eliza will eventually get together. They are already on that trajectory; in the most recent episode their future romantic relationship was heavily foreshadowed. The (hopeful) transition of Henry into a sexual being drew my mind to the only other Asian-American leading man on TV today: Steve Yeun as Glenn on AMC’s ‘The Walking Dead.’ The two share some striking similarities in how they are constructed as sexual beings, and by proxy, as men. Both Glenn and Henry are given very little backstory. In the entire run of ‘The Walking Dead’ all we have learned about Glenn—now one of the leading characters—is that he used to deliver pizzas for a living. Meanwhile, we know myriads of history about the white male characters, sexual and otherwise. We know little about Henry either—we get a picture of his mom and a brief scene with an ex-girlfriend in episode two, but both of those moments function to tell us about Henry in the present as a loner workaholic, rather than about Henry in the past. In season 2 of ‘The Walking Dead’ Glenn was often referred to not by name, but as “the Asian boy.” In ‘Selfie,’ Henry has yet to be given a last name. It isn’t until Glenn begins a relationship with Maggie (who is white, as is Eliza) that he comes alive, both a person with a name and as a hero. It seems that the same scenario will happen between Henry and Eliza; once their romantic relationship blooms Henry will become a recognizable and real being. This has already begun to happen. Henry’s most recent re-branding success is related directly to Eliza’s intervention. In the case of Henry and Glenn, both cases it is the role of white female sexuality that allows Asian-American men to exist as physical, sexual beings.

It’s clear that Henry and Eliza will eventually get together. They are already on that trajectory; in the most recent episode their future romantic relationship was heavily foreshadowed. The (hopeful) transition of Henry into a sexual being drew my mind to the only other Asian-American leading man on TV today: Steve Yeun as Glenn on AMC’s ‘The Walking Dead.’ The two share some striking similarities in how they are constructed as sexual beings, and by proxy, as men. Both Glenn and Henry are given very little backstory. In the entire run of ‘The Walking Dead’ all we have learned about Glenn—now one of the leading characters—is that he used to deliver pizzas for a living. Meanwhile, we know myriads of history about the white male characters, sexual and otherwise. We know little about Henry either—we get a picture of his mom and a brief scene with an ex-girlfriend in episode two, but both of those moments function to tell us about Henry in the present as a loner workaholic, rather than about Henry in the past. In season 2 of ‘The Walking Dead’ Glenn was often referred to not by name, but as “the Asian boy.” In ‘Selfie,’ Henry has yet to be given a last name. It isn’t until Glenn begins a relationship with Maggie (who is white, as is Eliza) that he comes alive, both a person with a name and as a hero. It seems that the same scenario will happen between Henry and Eliza; once their romantic relationship blooms Henry will become a recognizable and real being. This has already begun to happen. Henry’s most recent re-branding success is related directly to Eliza’s intervention. In the case of Henry and Glenn, both cases it is the role of white female sexuality that allows Asian-American men to exist as physical, sexual beings.

What is perhaps most frustrating about ‘Selfie’ is that both Gillan and Cho are so much better than the characters they have been given. Gillan’s timing is spot-on and she has a wonderful physicality that greatly enhances the comedy in her performance. Cho manages to convey a built-up energy under his straight-laced façade that is itching to be set free. The supporting cast, while also stereotypically constructed, are beginning to get some more screen space, adding depth to the superficially constructed office-relationships. There are moments in the show that gives one false-hope for its potential. Eliza tells Henry not to “get all slut-shamey” on her for her office romances, but her voice-over betrays her comment as she admits that Henry’s comments are valid. When visiting Henry at home, whom for all his talk about the importance of IRL relationships is usually alone, she cleverly quips “you live in a glass house”—which he does, literally and figuratively. Henry’s flaws are becoming more and more exposed, and one hopes that they will help balance the relationship between the two, although for the time being Henry is still given the moral high ground.

A more balanced relationship between Eliza and Henry, a less formulaic development of their eventual romance, and an emphasis the show’s moments of sharp writing instead of stereotype could go a long way in turning ‘Selfie’ into the show it wants to be, as well as the vehicle its stars deserve.